As the end of the decade approaches, recap and best-of articles abound. One such article that stuck out to me was a review of the decisions that shaped the Boston Red Sox over the last decade. The 2010s were a successful decade for the franchise. Their two World Series Championships and fifth best winning percentage in baseball (second best in the American League) put the Red Sox in the mix for the team of the decade. A lot of that fortune is a result of Ben Cherington’s franchise resetting decision to swing the waiver-deadline trade of Carl Crawford, Adrian Gonzalez, Josh Beckett, and Nick Punto in 2012. Carl Crawford’s tenure in Boston still bothers me.

When the Red Sox signed Carl Crawford before the 2011 season, I was ecstatic. Crawford had spent nine seasons tormenting the Red Sox as a member of the Tampa Bay (Devil) Rays. The image of Crawford taking a lead off first base likely keeps Jason Varitek up at night – 6 stolen bases in one game is incredible. While it might be hard to remember now given how things transpired in Boston (and then Los Angeles), Crawford was one of baseball’s best players for much of the new millennium’s first decade. In the years between 2002 (Crawford’s first full-ish MLB season) to 2010 (his last season in Tampa Bay), he accumulated 36.9 FanGraphs Wins Above Replacement (fWAR), a total that only 11 players surpassed over that timeframe; each of whom has a strong case for enshrinement in Cooperstown.

At the time of Crawford’s signing in Boston, it was reasonable to argue that he too was on a path to the Hall of Fame. On every player’s Baseball Reference page there is a list of similar players (overall, and by age) derived using Bill James’ similarity score concept. Below is the list of Crawford’s five most similar historical players through age 28 (his career before Boston), along with how many Baseball Reference WAR (bWAR) those players produced over their next six seasons:

| Rk | Player | Pos | SimScore | bWAR by Age | Total 29-34 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thru28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | |||||

| - | Carl Crawford | LF | 1000 | 35.6 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 2.4 | -0.1 | -1.0 | 3.8 |

| 1 | Roberto Clemente | RF | 926.5 | 29.9 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 8.2 | 8.9 | 8.1 | 7.5 | 47.0 |

| 2 | Sherry Magee | LF/1B | 911.6 | 43.4 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 2.5 | 15.7 |

| 3 | Sam Crawford | RF/1B | 904.2 | 39.7 | 5.6 | 3.3 | 5.7 | 4.7 | 5.2 | 6.2 | 30.7 |

| 4 | Cesar Cedeno | CF/1B | 899.6 | 44.2 | 5.1 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 1.3 | -0.2 | 7.9 |

| 5 | Tim Raines | LF | 897.4 | 42.1 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 6.3 | 3.8 | 1.8 | 21.7 |

Crawford, through his age 28 season, was most similar with three Hall of Famers (Clemente, [Sam] Crawford, and Raines) and two other really strong players.

Given things like that table, it is not hard to see what the Red Sox were thinking when they signed Crawford to a 7-year, $142-million contract. But as soon as they did things fell apart. In his first season with the Red Sox Crawford hit a dismal .255/.289/.405 (83 wRC+), only stole 18 bags, and had his worst defensive season (-3.6 UZR), which all worked out to essentially replacement level performance (0.3 bWAR; 0.0 fWAR). Career worsts all over the stat-card for him that year. My expectations were dashed, excitement gone with them, so all I could hold onto was that 2011 was an adjustment-to-Boston-year and that 2012 would bring the return of Tampa-Bay-Crawford. It didn’t. He got hurt, eventually needed Tommy John surgery and didn’t even complete two of his seven scheduled years with the Red Sox, as he was sent to the Dodgers in the aforementioned franchise-altering waiver deadline trade. He had something of a bounceback in his 2013 and 2014 seasons with Los Angeles, but he was never again the player we saw in Tampa Bay. The difference between Crawford and those similar players in the table above is that they kept producing after the age of 28, while he did not. The ~4ish wins (3.8 bWAR; 4.6 fWAR) are all he produced for the rest of his career.

Widening the scope from Crawford’s most similar players reveals how remarkable the end of his career is. Crawford is one of only 162 players who posted 35 or more bWAR (using bWAR allows me to take advantage of the Play Index tool) in their first nine seasons. Just getting to play in the major leagues for nine seasons is an accomplishment. Only 1,129 batters have received at least 150 plate appearances (PA) in eight of their first nine seasons. But playing and being as productive as Crawford was in his first nine seasons put him in the top 15% of players. But, just like his similar players, most of the other players in this small group kept producing, while Crawford did not.

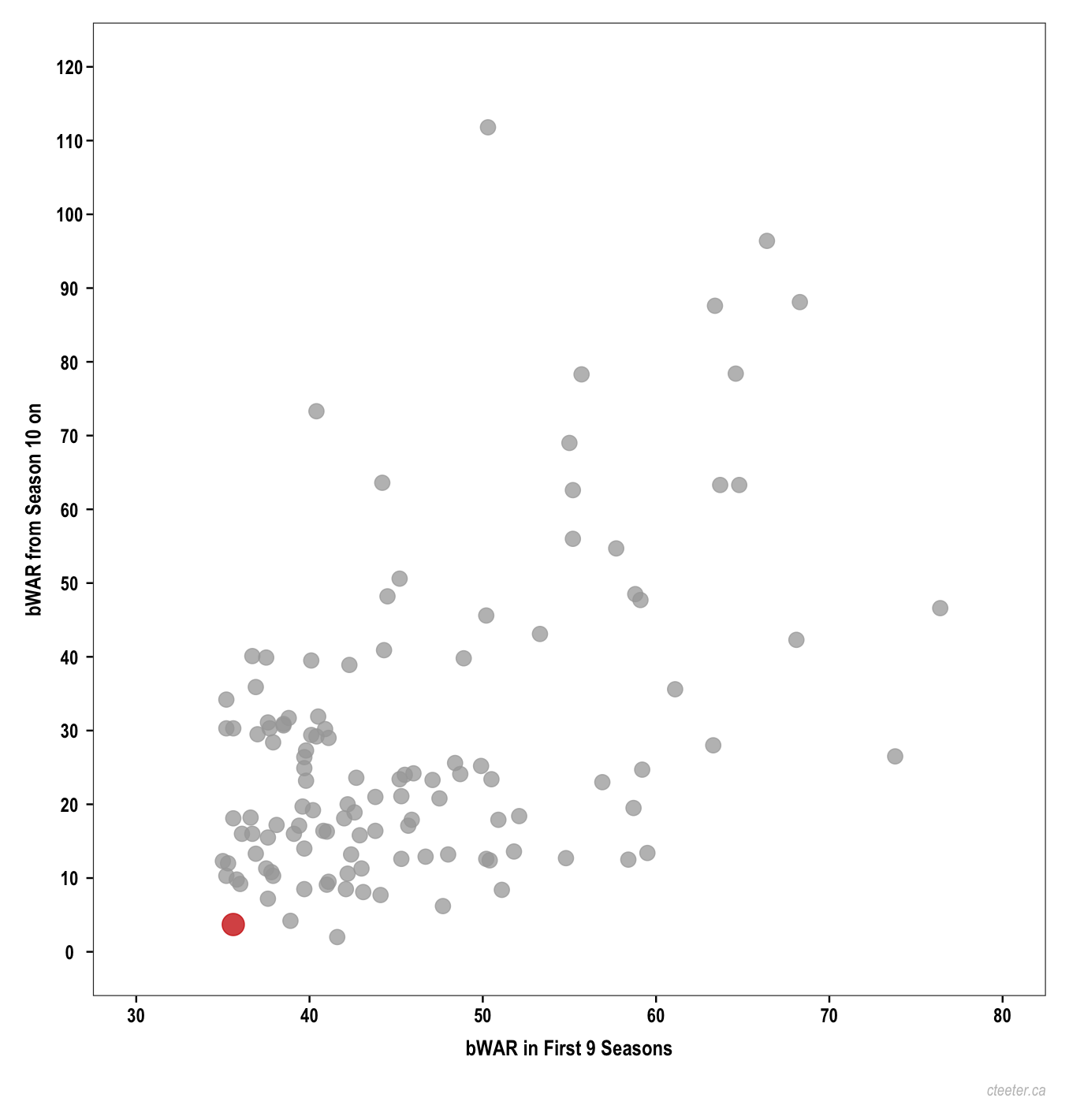

The plot above shows the relation between a players’ performance in their first nine seasons to their performance in their 10th season on for that group of 162 players who posted 35 or more bWAR in their first nine seasons and then got at least 1,750 PA from their 10th season on. As you can see, Crawford (the red point) produced the second lowest number of wins in Season 10 on (looking at things per 650 PA doesn’t change the story; see this for the order of Season-10-on performance). And ended up with the lowest career bWAR total among that group.

A truly remarkable stumble to the end of his career.

As I said, Crawford’s difficult time in Boston still bothers me. Obviously this is mostly driven by my Red Sox fandom. What happened in Boston and why does the Boston market do this to some players? At the time of his free agency, his shyness was often discussed, particularly how it made Boston a bad fit for him. An idea corroborated by Crawford after he left, when he said the baseball environment in Boston was toxic and pushed him into a depression. Boston was (possibly) his darkest timeline. Regardless of team fandom, Crawford’s abrupt decline was junk for baseball reasons. We didn’t get to watch a dynamic player who seemed destined for greatness (or at least really goodness) do his thing anymore. I wonder how his career would have played out had he stayed in Tampa Bay. Would we be discussing his Hall of Fame candidacy? I think we would. Instead I have spilled a bunch words and tables and figures to show just how terribly things ended for him after the promising start and damn that sucks.