Magnus Carlsen got what he wanted. Or at least that is what I infer from his behaviour in Game 12 of the 2018 World Chess Championship. He had a winning position on the board and an opponent with only a few minutes left on the clock, but he offered a draw, opting for today’s tiebreaks. Carlsen and his team must have figured that he was a huge favourite in the tie breaks; FiveThirtyEight’s Oliver Roeder, who has posted win expectancy figures for each game like the ones I have, suggested Carlsen was an 80% favourite to win the tiebreaks. But even if that is true, given the situation in Game 12, I think he should have pushed a little harder to win the game and wrap up the championship.

Let’s look at it from a perspective of expected prize money. The championship has a £1 million prize fund that would have been split 60/40 had the match ended in regulation time, but because the match has gone to tiebreaks it will be split 55/45. If we accept the 80% estimate of Carlsen’s likelihood of winning the tiebreaks, then his expected prize is £530K. With a little algebra we can determine Carlsen’s expected prize from the situation on the board in Game 12 and find the win estimate that Carlsen would have needed in Game 12 for his expected prize to be higher than the £530K from going to tiebreaks. If Carlsen felt his winning chances were at that level or higher he should have pushed for the win.

Let’s say that Carlsen thought the position on the board in Game 12 was likely to end in a draw 75% of the time – quite possibly a low estimate given the outcomes of Games 1 - 11. Regardless, if he thought a draw was 75% likely, then he only needed to estimate his likelihood of winning at 16.25% to match the £530K expected prize return:

Any estimate of winning Game 12 higher than 16.25% means Carlsen’s expected prize is higher than that expected from going to the tiebreak. I find it hard to believe that his winning chances were lower than that 16.25% mark (assuming the 75% draw likelihood). Of course, this is just one possible outcome. A similar exercise can be done for any combination of the likelihood of winning the tiebreaks and the likelihood of Game 12 ending in a draw. I don’t think, nor do I expect that Carlsen was sitting there doing this sort of expected prize money math to determine if he should press Caruana in Game 12, but I expect that prior to the game he and his team discussed what they felt his chances of winning the tiebreak were and would have had a plan for how hard to push for a win in Game 12 should the opportunity present itself. If they did not, then they were not adequately prepared.

But all of that is mostly moot. Carlsen won the rapid games in dominant fashion and retained his title as Chess Champion. Many have suggested this result justifies his decision to offer the draw so early in Game 12. Unfortunately, that is not how decisions work and not how we should evaluate them. Evaluate the process that drove the decision, not the outcome. Carlsen seems to (sort of) understand this. In response to a question during today’s post-match press conference that was begging him to agree that his win justified the early offer of a draw in Game 12, Carlsen said:

This conclusion shouldn't necessarily be based on this result. It should be whether you've made a good decision or not and based on the information I had at that point I think I made a very good decision.

Carlsen’s ability to win the rapid games did not change as a result of him offering the draw after move 31 in Game 12. It remained the same. His perceived advantage in the rapid format represented a safe cushion on which he could land should his pushing for a win in Game 12 not work. If he really felt he could not win Game 12 then his early offer is understandable, but it flies in the face of the situation over the board. So much so that chess.com set up a round-robin tournament of chess engines starting from the position at which Game 12 was drawn. At one point today, Black (Carlsen’s side) had won 10 games, White had won 2 (reportedly when weaker engines were playing better ones), and there were 13 draws. Maybe the 75% draw estimate I used above was actually too high, rather than too low.

I should be clear that I don’t think there is anything wrong with Carlsen opting to move the game to the format that strongly favoured him; that is a reasonable strategic decision. And I am certainly not advocating that he push for a win at all costs. That would be completely silly. I just think he gave up on the win much too early and in the end it (possibly) cost him £50K.

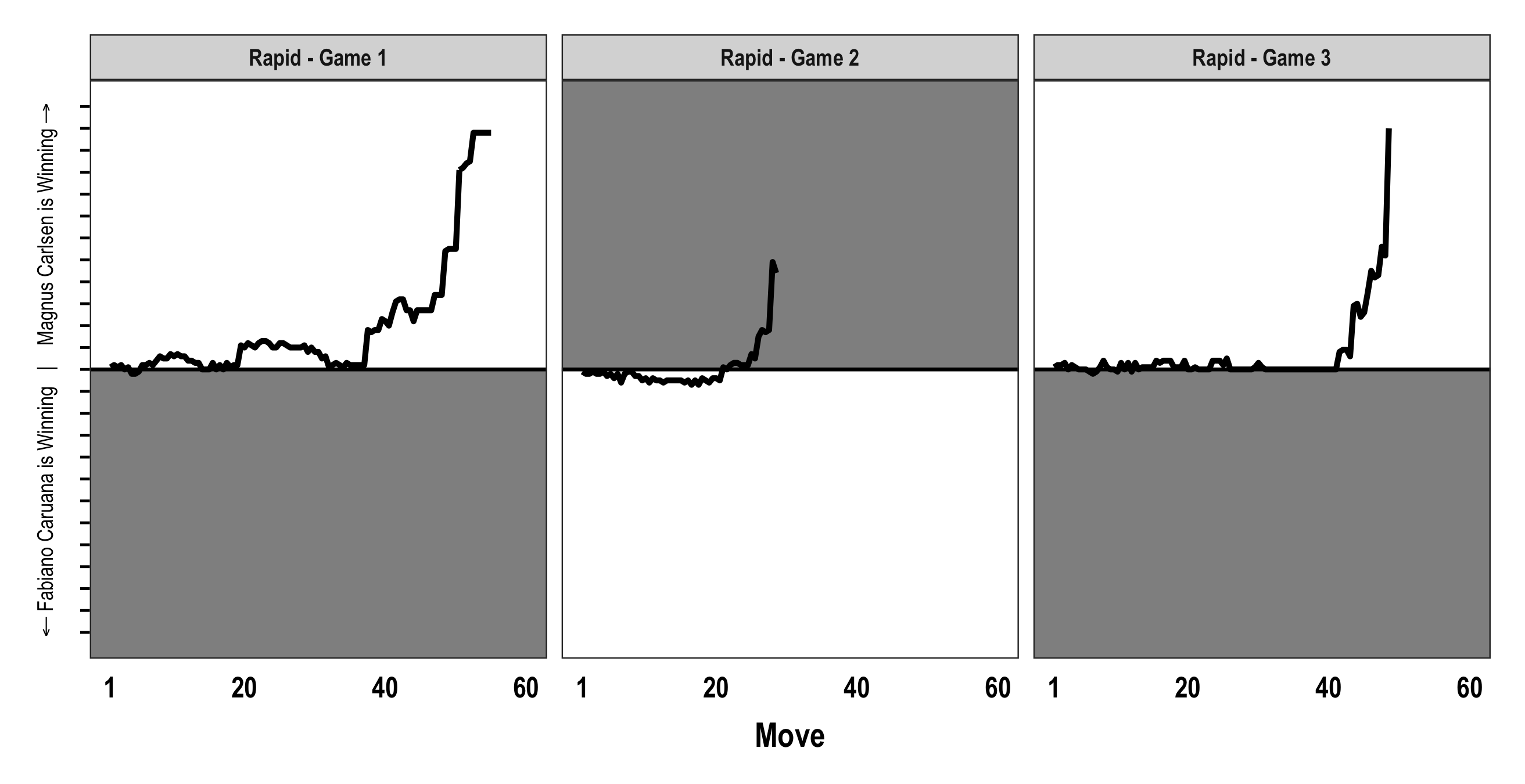

But enough of all that, here is how the games played out (note: the y-axis ranges +12 to -12 here rather than the +5 to -5 I used for the figures in my posts on Games 1-8 and 9-12):

You can see how Carlsen just pounced on key Caruana mistakes in each game and drove things decidedly in his direction. The advantage Carlsen had in Game 3 is actually off the plot. He was +12.6 on move 49 and then +64 for moves 50 and 51.

I thoroughly enjoyed watching this championship. Digging into the games has re-motivated me to improve my game.