Last Wednesday it was reported that the co-owner of the Orlando Magic, Pat Williams, has dreams of bringing a major league baseball team to Orlando. Williams even came prepared with a photoshopped Little League logo for his Dreamers. Rich people are going to do rich people things, so maybe this is not worth getting worked up about, but the notion of putting another major league team in Florida is puzzling. The people of Florida are barely supporting the two major league franchises they have now. In 2019, Tampa Bay and Miami ranked 29th and 30th in attendance per game. Even if you combined them they would have only ranked 18th. These teams are simply not supported at the ballparks.

Last year, the Rays won 96 games and made the playoffs, but they did it in front of a mostly empty Tropicana Field. There is no disputing that the Rays have struggled to compete in many of their 22 seasons, but even during the seasons in which they were winning (or close; i.e., >= .480 win percentage) the best they have ranked in home attendance per game is 22nd. In 2008, when they won 97 games and went to the World Series, they ranked 26th. The Marlins are much the same. Over the franchise’s history, their median home attendance per game rank is 28th. In their World Series championship years of 1997 and 2003 they ranked 11th and 28th, respectively. The offseason gutting of that 1997 championship team likely killed baseball in Miami for good.

But, hey, maybe team quality is not the thing that will bring Floridians out to the yard. Maybe they want to watch a star. Maybe even a star who is chasing a record. How about a League MVP who is mashing home runs at a historic rate? The Marlins had that in Giancarlo Stanton. You may recall that Stanton played for the Marlins from 2010 - 2017, before old pal of the Yankee franchise and current Marlins CEO, Derek Jeter, sent Stanton to the Yanks for a not-really-great package of prospects.

In 2017, his last as a Marlin, Stanton became the 44th player to hit 50 home runs in a season; Aaron Judge hit 52 in 2017 to become the 45th and Pete Alonso hit 53 last year to become the 46th player to break the 50 mark. Stanton had 26 HR at the All-Star break and there were rumblings of him chasing down Roger Maris’ real HR-record of 61. Idiocy of the real HR-record part of that last sentence aside, Stanton’s push to get to 60+ HRs was compelling! And to make matters even better, the Marlins were not completely terrible. Did these things bring people to Marlins Park? No. The Marlins ended up ranked 27th in home attendance per game that year. Basically the same as any other year.

Thanks to the wonder that is BaseballReference.com I was able to dig deeper into team attendance numbers in the years they had a player hit 50 or more home runs in order to compare Stanton and his 2017 Marlins with similar company. Some of the 50 HR seasons came in years where fewer folks were pushing through turnstiles to see major league baseball games; things were a little different in 1920 than they were in 2017. So in an effort to be making fair attendance comparisons, I am only including seasons in which the league averaged at least 1.5 million fans per team over the season, which ends up being between 1990 and 2019 (29 of the 46 50+ HR seasons).

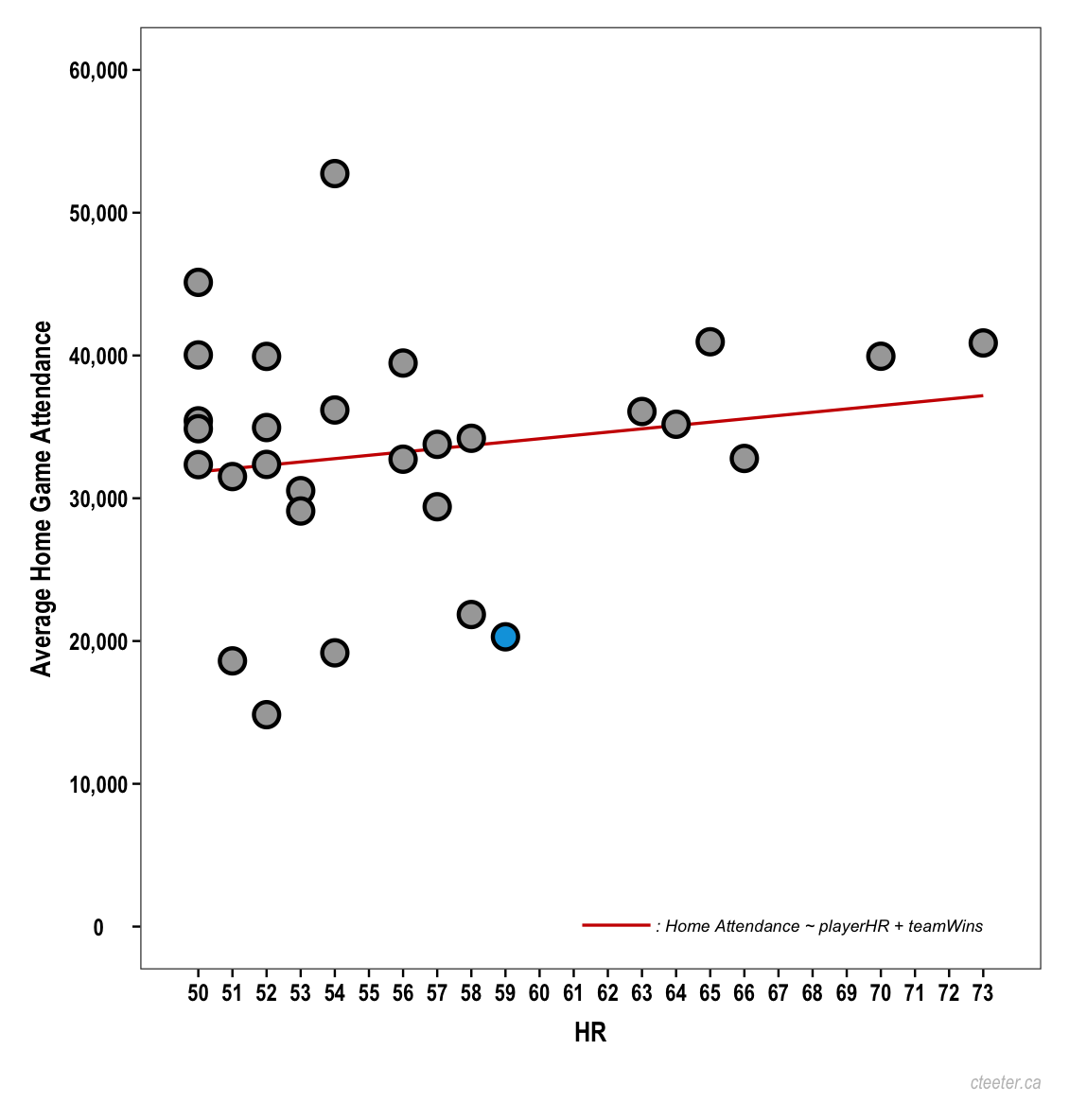

Below is a scatterplot of the player’s team’s average home attendance by the number of HR they hit (Stanton’s 59 HR season is shown in Marlins blue):

Really not great for Stanton. His time hitting 59 bombs for the 2017 Marlins wasn’t the worst supported effort we have ever seen for a 50+ HR guy (congratulations to Mark McGwire and the 1996 Oakland Athletics), but it was close. On the plot, I included a reference line for a model that predicts attendance from the player’s HR total and their team’s win total. As would be expected, the team’s win total does most of lifting, but the player’s HR total does account for some of the variance in attendance. The model is not great (r2 = 0.187), as the sample is small, but pressing on and using it to get an attendance prediction for the 77-win 2017 Marlins and their 59-HR hitting slugger gives 31,980. The Marlins actual average home attendance in 2017 was 20,295. That is the sixth biggest absolute discrepancy between the predicted and actual attendance numbers; fourth biggest overprediction. You can spot the other big misses in the figure. People did not show up in anywhere close to the numbers that might be expected.

To keep beating this dead fish, the 2017 Marlins finished with the sixth lowest proportion of seats filled at home (on average) and did so with the second smallest stadium capacity (Marlins Park holds 37,442). They had the second fewest seats to fill but still only filled half of them (on average) in a season in which they were competitive(ish) and had a slugger slugging his way up the single-season HR charts. More insult: the Marlins had the third largest Home - Away difference in average attendance. The numbers are damning. While I hate Stanton being on the Yankees, the silver lining is that at least more eyeballs will be put on his abilities. Highlights and the internet can keep us closer to the game than ever before, but having a star like Stanton, who is capable of hitting 60 HR in a season, playing in a place where people actually go to games might help generate more (young) fans of the game. Even if they become Yankee fans, that seems like a good thing for baseball.

This is certainly an overwrought analysis to remind everyone that people are not attending baseball games in Miami (nor in Tampa Bay). And maybe it is unfair to paint the whole state of Florida with Marlins’ and Rays’ attendance blues, but what makes one think Orlando will be any different? Looking at the Magic’s attendance per game does not inspire much confidence. Since 2009, a timespan in which they have made the playoffs four times, the Magic have finished in the top half of the league twice.

If the powers that be in baseball want to expand (which they shouldn’t) or move a team to a new city, they must focus on putting that team somewhere people might actually attend games (i.e., not in Florida), and not just the next city whose taxpayers a billionaire wants to bilk into building him/her (another) stadium.